by E J Delaney

When the klaxon kicked in, a detective’s first thought would have been, Murder.

Well, maybe not their first thought. Few would have known what the wailing signified, and even then it was a leap from opportunity to motive. But that’s the line their investigation would have taken. Honed by the intense tunnel-visioning effect of godspace, any sleuth worth their deerstalker would have seized upon that first breadcrumb and made straight for the dead body.

My reaction was to punch the bulkhead.

“Not again!” I keyed the intercom and brought the cargo up to speed: “Attention! Attention, all passengers. Please remain in your booths. Repeat, remain in your booths.”

As if they would.

“It’s the Arrow Drive,” Poole reported. “Same as last time. It hasn’t disengaged.”

I relayed the information. “The Delahaye is still in godspace. Repeat, we are still in godspace. For your own safety and sanity, please remain isolated while Vice-Captain Poole and I resolve the malfunction.”

Poole cast me a look, their one organic eye narrowed behind its burnished aluminium faceplate. Why would I bother with the passengers? As captain it was not only my duty but also my psychological imperative to focus on the ship.

“Patch the damage,” I instructed. “If it really is the same, there’ll be a killer on board. That’s not something I’m going to tolerate.”

The problem, to put it in that same nutshell we’d had cracked en route to Sesquipedalia, was that our revered leaders—the latest dishwater scum of politicians and bureaucrats—had rendered g-class vessels inherently vulnerable to sabotage. (I’d said ‘malfunction’ but that was a euphemism.) Government excises. Civil liberties. Where the long ebb had left us perennially underpersonned, the flow-on was mandated pandering. In recompense for constitutional deprivations visited upon them in godspace, passengers were at other times to be afforded every luxury of movement.

I cut the alarm. “Big picture, Silas. You get us back to bogspace, I’ll keep us palatable.”

Poole saluted. “Konprann, Captain.”

Silases aren’t always the most expressive, but two traits they convey well are grit and fortitude. Poole’s face was a steely rictus (no pun intended), shoulders set like a weighted barbell as they marched off to examine the engines. I followed after them, equally determined in my own manner.

People were already leery of the Arrow Drive; if we had any more mishaps, we’d forfeit our safety rating altogether and be barred not only from the lucrative corporate runs but also from such bread-and-butter jobs as our present engagement: the off-peak special to Gabor II.

Six passengers, a brace of crew, bound for a far-distant resort planetoid.

One weasel in our midst.

Not that I cared so much about human life—not in my heart of hearts, where I was captaincy incarnate—but the loss of cargo was a breach of our integrity, every bit as damning as being flotsam blindsided or boarded by pirates.

The Delahaye was my ship. Mine. Whoever had done this was going to pay.

“Frape wòch, fè etensèl,” I vowed. “Fè flanm!”

The words dropped in a flinty whisper, loud enough only for Poole to catch in enhanced playback, losing half a step to translation. Strike rocks, make sparks.

Make flames!

Halfway down the craw, I cut clear and strode toward the passenger booths.

#

None of us can help how we act in godspace. It was a pity, then, there was no one on board to represent the Civil Liberties Authority. I’d have enjoyed punching them in the gut.

I say ‘enjoyed.’ That would have come retrospectively, divorced from my overriding instinct to protect the Delahaye and make good on the compacts of flight. In the moment, I’d have felt nothing but rage.

For years, the CLA had campaigned to outlaw passenger restraints. (Never mind the murders, rapes and suicides that would result.) If pilots aren’t subjected to it, they argued, why should anyone else be? To which those with even an ounce of common sense gritted their teeth and replied: (a) pilots can’t be restrained and still operate the ship; and (b) pilots live to fly. That’s why they become pilots. It’s their inner crux and will inform their every behaviour. They alone are the angels of godspace.

Be that as it may, the CLA insisted, all flabby jowls and flagpole tumescence. We are, every one of us, entitled to life; liberty!

When challenged to step down from this soapbox—to resume the discussion in godspace, free and unfettered—the board did finally demur. Of course (they allowed) some degree of restriction was necessary... but only for the duration of the jump; not a second longer!

It was a stipulation from which there arose the noose-shaped loophole we’d twice now found our necks stuck through. Whereas the activation of passenger restraints was hard-linked to the Arrow Drive’s initiation, the unlocking of such restraints derived not from the drive’s cessation but rather from our arrival at a designated endpoint. The procedure was automated, all oversight foresworn. Thus, should a g-class ship complete the divine leg of its journey but prove unable to revert from god- to bogspace, the duralumin bands would roll back regardless, freeing the inmates.

Like I say, if there’d been a CLA man on board, I’d have unleashed the wrath of Adjassou-Linguetor upon him—not because I’m deep-down brutal, but for the sheer temerity he’d shown in jeopardising the Delahaye.

When it came to that sort of liberty, I could be very free with my fists.

“Sòt pa touye w, men li fè w swè,” I muttered, echoing my grandma’s wisdom as I swept through the passenger section. Beyond the bogspace lounge, I could see the booths had their doors open. The cargo was loose, mental conditions unknown. Stupidity won’t kill you, but it sure makes you sweat.

You got that right, Grann.

Granmè Asefi never went into godspace, but I bet she wouldn’t have needed restraints. She was mindful, my Grann, and what you saw was what you got. If forced to reveal her innermost self, she’d have cooked chaka and told her stories, just like always.

I tongue-clicked the communicator. “Silas?”

“Here, Captain.” Their voice in my ear sounded calmly furious. “Sabotage confirmed. Rat bomb on a timer. Half the quantum fletching’s been shredded.”

And there it was: Sesquipedalia redux. Twelve months on, circumstances had contrived once more to disable the arm-, leg- and neck-clamps while we were still in godspace. Same ship, same shit.

It was a mad act. Nobody in their right mind should have wanted to; anyone who did ought to have stayed locked up (CLA presumptions notwithstanding). But such was the design flaw. Until the Arrow Drive was disengaged, whoever had planned this was at liberty to act while manifestly non compos mentis.

“Do what you can,” I told Poole. “I’ll check the human cost, see which of our six is the snake in the henhouse.”

I curled both fists, foregrounding the VOO and DOO tattoos on my inner knuckles. My hackles straightened from their warrior’s crouch. One of our passengers had made themself a murderer. They’d done it aboard my ship; to my ship.

In my current state of mind, I found that unforgivable.

#

The first passenger I came across was the crime novelist, Eva Jane Daintree. Middle-aged, face crinkled with mirth lines. She wasn’t obviously psychotic—not violent or sex-crazed—but she evinced a palpable fizz as she threw herself beyond the mock-walrus club chairs and into my orbit.

“Captain Judd!” She was perhaps one part repentant to eighty-seven parts bushy-tailed. “I know you said not to but I just had to get out. The Arrow Drive! Brigid’s flaming light, I never imagined. They warned us what to expect, but this— this is so much better than a sea change (or whatever Gabor II was meant to be; my agent’s a darling but vague as a mojiblur). Too much to write down. Plots, people, sensations. I need to screenshot it, do you see? In here.”

She gestured at everything and nothing, tapping the side of her head.

I stepped past her. “Yes, Ms Daintree.”

“Oh my god, your hair.” She reached out, thought better of touching me. “It’s perfect. Perfect. Your skin, too, of course, but your hair. The symbolism! Space-dark, braided to show discipline. But if you set it free you’d have all the energy of humanity flung loose. Through woman, unbounded. The species rises!”

While I did my best to ignore her, she attached herself to me like the most garrulous of sidekicks. At least she was benign. Eva Jane’s mainstay was creativity, that much was clear: a bubbling brew of articulation. She’d burst all her inhibitions—everyone did in godspace—but she wouldn’t have cause to feel ashamed of it.

Passenger #2, I wasn’t so sure of. Slick Johnson, his name was. A real estate pimp, narcissistic AF. (Shagreen suitcases with laminated peacock feathers and cubic zirconia. Silver nanowire eyebrows.) He exited the second booth, strolling with such brazen nonchalance that I had to look twice—although I’d really rather not have—to confirm he was naked.

“Well that can’t be unseen,” Eva Jane noted. “Phallic rocket-ship imagery. Organic sag, pump action. Man, too, shoots for the stars.”

Or to put it more prosaically, in the buff and tugging at his erection. The deed seemed almost absent-minded, as if he fell to it as a matter of course whenever he had a hand free. His face lit up when he saw us. Condos to sell, sheep to fleece—the Wolf of Gabor II.

“Ah, ladies! Johnson’s the name. Slick Johnson. I wonder if I could interest you in—”

“Put it away, Mr Johnson. Put yourself away. There’s a killer on board.”

“A killer?”

Abandoning his spiel, he spun about and vanished back inside the booth, still languorously wanking. Not a murderer, I thought. Just a man with a much-exercised ‘me’ perspective.

“Buns away,” Eva Jane observed.

We continued on up the corridor.

Passenger #3 was the marine biologist turned activist, Hasini Chitrasena. When I’d welcomed her aboard, she’d been upbeat and passionate, telling me about her work with the Gaborian hermit crab. Now she sat on her recliner, limp as a doll and crying softly to herself. She wasn’t hurt; not physically. Her soul was just keening from the depths.

Was it the futility, I wondered? Her foetal despair the inevitable by-product of species endangerment carried off-world? She was evidently a strong woman—she’d have to be to keep on fighting—but godspace leaves no illusions. Each transit to or from the battlefront would lay bare such knowledge as she’d buried at the back of her mind; that kernel of helplessness she kept wrapped in never-say-die pugnacity:

People don’t change; not at the multi-maggoted core where Homo sapien defiles not only his own Mother Nature but also those of a hundred other planets. Vale the Gaborian hermit crab (be it next year or in a decade’s time). Vale hope, vale deliverance.

And again, it wasn’t that I cared for such things. Cloaked in godspace, I thought about them only insofar as to dismiss Hasini Chitrasena from my list of suspects. Like a blind woman brushing my fingertips across her face, I evaluated and moved on.

“Shouldn’t we do something?” Eva Jane ventured. She’d poked her head through the doorway, the question posed in tremorous sotto voce.

“No threat,” I declared. “Not relevant.”

Harsh, perhaps, but that’s how it was. In bogspace, I’d maybe have behaved otherwise; with the Arrow Drive powered down, making our final approach under sub-g propulsion. But not in godspace. Here, my focus was as pure as motion itself. Where the physics were single-minded, so too the carbon particles masquerading as people. So long as the Delahaye wasn’t affected, I literally couldn’t have cared less.

I pushed past Eva Jane and along to the next cubicle.

Passenger #4 was, if anything, in a worse state than Hasini Chitrasena. This was the actress Peach Tattie-Luger, a sweet, prune-faced septuagenarian who, Poole informed me, had made history as the first woman to play both Janet and Dr Scott in The Rocky Horror Show (separate productions). She was a force of theatrical nature; yet, that which bogspace highlights, godspace turns dark. However much poise she’d brought to the stage, the doyenne of Drury Lane now threw herself like a deranged cardinal at the confines of her booth, slapping at its upholstered vinyl walls and croaking, “Who am I? Who am I?”

“She’s acting, right?” Eva Jane looked to me for reassurance I couldn’t give. “She’s Peach Tattie-Luger.” Feeling this was the right answer, she called it out: “You’re Peach Tattie-Luger. You’re brilliant!”

Her words had no effect. The haggard thespian kept to her stomping and staggering, arm giblets aflap as she raked bony fingers through her hair. “Who am I?”

“Leave her,” I advised. “If you want to be kind, forget you ever saw her this way.”

“But—”

“She’s not the one.”

My lack of compassion went against the script, but I couldn’t help that. Just as Eva Jane couldn’t help hurrying after me.

“What do you mean, she’s not the one?”

“The psyche has its devils, Ms Daintree. Little red dyab yo tormenting with their pitchforks, driving Miss Tattie-Luger and those like her to curl up and cower. But it also has demons—djok mawon who rise up in godspace and turn their evils inside-out upon the world.”

“So all this—” Eva Jane gestured again at herself and her outlook. “The rush. The ideas. This cornucopia. People feel it differently?”

“Like ripeness and rot.” I stepped up to cubicle #5. “For you, the horn of plenty. You’re lucky, well adjusted. For others—”

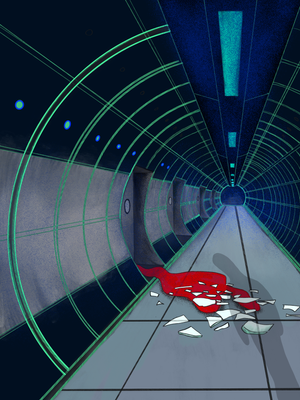

I shouldered past the door and felt my muscles bunch. My eyes smouldered at the broken, lifeless cargo within. Here lay evidence of the demons’ work; of the mad creature who’d put my ship at risk.

I muttered an invocation to Erzulie Dantor.

“For others, it’s swallowed shards of the looking glass.”

#

When I’d met Maddison Suet D’Amato and her husband in the passenger lounge prior to lift-off, she’d seemed timid, demure. She had a gymnast’s build but no trace of performance; a cowed tilt to her chin.

In godspace she’d been a fighter.

“I don’t know how to feel about this,” Eva Jane admitted, peeking past my elbow. “Her arms, neck. The bruises on her throat. They’re like burning soot. Chimney smoke. And those eyes!”

I nodded my understanding. They were dead eyes. Angry eyes.

“Like someone’s taken a frog and squeezed. Oh god! And here I am, just soaking it in. Staring at her. And she at me! Woman. Corpse. And in my head I’m setting it all down. Preserving it.” She made a gurning, retching sound. “What I should be doing is vomiting. Brando and Bertolucci, I should be heaving up everything I’ve eaten for the last week; only, I’d want to describe that, too.”

“Devils, Ms Daintree. Demons.”

I felt my mass held in balance against the presence of the ship. Muscle. Bone. Mother and daughter. In godspace I was anchored, the Delahaye pushing back at me with the same unquenchable force as the grounded strike of my spirit.

I turned from the cubicle.

“Where are you going?” Eva Jane fretted. “Shouldn’t we—?”

She waved helplessly at the victim I had no time for.

“Come,” I told her. “You’re my witness.”

Not, in fact, that I required one. Aboard ship my word was law; doubly so beyond bogspace. The only proprieties were what Poole and I judged fit.

And Poole and I had no choice.

What is free will? a philosopher might have asked, confronted with the occupant of cubicle #6. If none can influence the way godspace affects us, can we be blamed for the goings-on that occur there?

I cared not a jot. No denouement was necessary to make the Delahaye secure; no unveiling of culprit in the ship’s library.

I stalked into the padded cell. The upholstered vinyl walls cast cherry starlight upon the empty recliner. Runnels coursed the tang-blue carpet, back where the beast had dragged itself.

Carlo D’Amato wasn’t a big man. He’d thought he was, maybe tried to be. He squawked when I bent down and grabbed him by the shirtfront, his skittish lips already framing an excuse. (Sezi kou berejèn, my Grann would have said—ironically though, before dropping one into the pot. Surprised as an eggplant.)

“I didn’t mean to,” he gabbled. “I only wanted to tell her. To show her. In godspace, where she’d have to believe it. Capisci? We were in love! Nothing wrong. Not like she was saying. No need to go to her mamma, her papà. All she had to do was listen, then two weeks on Gabor II for me to show her. In bed. On the beaches! But no. No! She was talk, talk, talk! ‘No, Carlo. Get away from me, Carlo.’ No listening, not like she was supposed to.”

I lifted him off his feet. “You sabotaged the Arrow Drive.”

D’Amato’s snakeskin shoes scrabbled half an inch above the shagpile. “How could I know she’d turn crazy? Love, I tell her. Love! But she is ‘No, no, no, no, no.’ And backing away. Just pazza. Pazza, I say! Wouldn’t hear me. Wouldn’t let me touch her.”

He was like a rooster with its chin drawn back, culpability lodged in its gullet.

“And then she slaps me. Me! Oh, my tesorino.” His Adam’s apple scraped against my knuckles. “My beautiful, stupid amorino. Why wouldn’t you listen? Why did you make me?”

“You killed her,” Eva Jane whispered. She looked to me, the shock in her voice already segueing to fascination. “Can they convict him for that? Intentionally bringing about something he couldn’t control? I mean, what would you even call it: premeditated accidental murder?”

“Mande mwen yon ti kou ankò ma di ou,” I murmured, thinking of Granmè Asefi. Ask me a little later and I’ll tell you. I clicked the communicator once more. “Silas? I have the perpetrator. How long for repairs?”

“Half a unit, Captain. Plus half again to run simulations.”

I closed my eyes. The need pulsed all around me, an interlocked infinitude of spherical cross-sections blossoming from my innermost point. Rotating. Sheathing. Wilting like armoured petals. The layers closed over me, the skein of validation binding my actions to the Delahaye—forever and always.

“Understood,” I told Poole.

Amidst my resolve, I was conscious of D’Amato’s jabbering denials; his self-serving anti-omertà and the feeble circles he made with his upturned hands. I caught the phosphene glint of his CD’A signet ring, felt the animus behind his words: blaming his lost love; railing against godspace and its fomenting of the weaker sex.

When I snapped my eyes open, my pupils were as wide and cold as the universe.

I showed him the demon inside.

“Should we tie him up?” Eva Jane was asking. “Take down his confession? I mean, I can see that he did it. The guilt’s like a cringe. A coat he can’t take off. But later—”

“There is no later.” I released my hold. “We’re all of us guilty; we’re all of us justified. Godspace is its own jury.”

“That’s right,” D’Amato yammered. He reeled, trying to find his feet. “I had to do it. I didn’t want to but—”

I hit him. With all the power it took to punch beyond bogspace, I drew my fist back and slammed it into the fragile bone carapace of his throat.

His windpipe shattered. He fell to his knees then onto his side, a gasping chalk outline with carbon shading.

“Murder,” I conceded, “is a grey area. But sabotage falls under maritime law. Captain’s prerogative. CLA be damned.”

Eva Jane leaned forward, studying D’Amato as he clawed for breath.

“A capital offence?”

“By definition. Stamped and sealed with the corpus delicti.”

Which was all well and good, and yet I couldn’t help mourning the Delahaye’s safety rating. My cheek muscle twitched as I pictured us grounded in a banishment of bureaucracy, perishing alongside the displaced hermit crabs.

The notion left me cold. Yes, humanity had pulled at the galaxy’s sleeve. We’d had the effrontery to spread our seed amongst the stars. But was disdain truly the best we could hope for; indifference while we evolved beyond our base components?

I caught a flicker then of future potentiality: of Poole seated at their station, flesh lost in shadow and their chrome conflating; of the Delahaye set free, sloughed of organic blight.

My baby taking wing.

“Godspace giveth and godspace taketh away,” Eva Jane suggested.

“Yes,” I agreed.

I nudged D’Amato with the toe of my boot. We were talking at cross-purposes but he was dead all right, a human bruise lying as still now as the silence that follows the Strangler’s Lullaby:

“A knot to untangle / a knot to untie,” I intoned. “When is a knot / not a knot / When you—”

“Die,” Eva Jane finished.

We stood there awhile, sharing this singular point of reference. Me. Eva Jane. Carlo D’Amato. Three absolutes, our dominions overlapping. Had I done right? Would the run to Gabor II be our last, as it had been for Maddison Suet D’Amato?

I clicked my tongue. Intangibles be borked, wi! For now, we still had to get to Gabor II. (Sixteen hours at sub-g, assuming we were able to de-Harrow.) Like the inquest, morality could wait.

“Silas?” I queried. “Is it done?”

Poole saluted my ear drum: “Affirmative, Captain. Repairs complete. Sims are green.”

“Acknowledged. Disengage the Arrow Drive.”

I gave the order without hesitation, before my brain could process the upshot. That was the only way: concentrate on the now, not what lay ahead; like cutting the hot water flow on a shower whose long-fingered caress was keeping winter at bay.

“Konprann, Captain.”

As much as it could, Poole’s voice conveyed a martyr’s nirvana. I counted silently in company with the hangman: Three ti poulèt yo, two ti poulèt yo, one ti po—

From light and dark, greyness descended. Its membrane closed around me as the Delahaye plunged back into bogspace. My focus broadened; peripherals intruded (I tried but failed to fight them off). I wondered for the thousandth time whether the cascading plunge of my stomach marked truth’s return or its wrenching, unendurable loss.

I found myself on my knees. Eva Jane lay doubled-up beside me, her face twisted into a morning-after expression.

“Uck. That was— that was horrible. Unmitigated blogarrhea. And— and I didn’t care about any of it. I mean—”

“You and me both, Ms Daintree.”

I shifted my weight, freeing one hand to coddle her shoulder. I could do that now, captaincy taking a step back. In the other booths, I knew Slick Johnson would be putting his sheep’s wool back on; Peach Tattie-Luger her mask. Hasini Chitrasena would pick herself up and blow fire from the embers. We each of us persisted, as true to ourselves as awareness would allow. Only Carlo D’Amato and poor fierce Maddison lay without dissemblance.

“For a man’s wounded pride.” I jerked my chin in disgusted lament. “Mr Poole?”

“Here, Captain.”

“Flags at half-mast, please. Take us in.”

“Acknowledged.”

And so it was that our certainties faded. (For some, relief; for others, regret.) Plugged in to the secondary controls, Poole turned the ship’s nose, orientating us in-system. Those secrets that had played out in godspace, we consigned to the mist and murk of memory.

Kreyòl pale, kreyòl konprann; kreyòl vole, Grann would have said, too wise a woman to weep over paradise lost. Speak Creole, understand Creole; Creole flies away.

For a moment I clung on. I held tight to the fading dream, wisps of profundity slipping through my fingers. Then reality subsided, as it always did.

With devils stowed and demons in the hold, we began our approach on Gabor II.

###

© Copyright 2025 E J Delaney

About the Author

E J Delaney is a speculative fiction writer living in Brisbane, Australia’s River City. E J’s short stories have appeared in Daily Science Fiction and the podcasts Cast of Wonders and Escape Pod, as well as the Reinvented Detective anthology and in limited edition print collections from Air & Nothingness Press. E J has thrice been shortlisted for Australia’s premier speculative fiction accolade the Aurealis Awards, in 2021 winning in the category of Best Fantasy Short Story. www.ejdelaney.com