by Brendan Craig

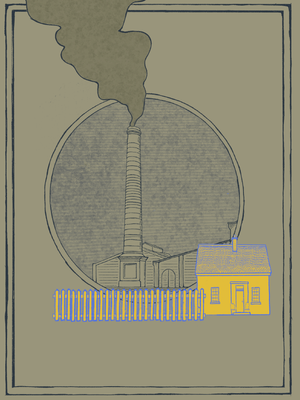

When we first came here to this foreign place, we were new — we were strange. Four chimneys defined the town’s centre; grey-black pillars rising towards their own dark cloud against the night sky. We were welcomed and we were watched. Ambiguity can also be truth, that is certain. And my memory is failing me, but I believe that the man in the olive overcoat was already there too. I see him through that child’s eyes — rising from the dirt, still as a tree.

I could feel the tension between my parents in those small days, even as its meaning slipped past me. I felt like a pebble in a rushing stream. We had left behind flames, broken buildings, bodies on the street. But I did not understand, until many years later, what my parents had fled, or why this new, odd little town offered such a mixture of hope and uncertainty. Everything back then seemed to be reaching towards the sky. The chimneys. My father’s fledgling fruit trees. The odd man in the long overcoat.

I asked him once what he was doing, standing there in the dark, deep into the night, notebook in his stubby hands. I always thought his hands belonged on a child; that somewhere else the universe compensated, and perhaps a child was being teased for large square paws that hung monstrously from puny wrists. I asked him once what he was doing, and he turned slowly to look down at me. I was frightened by his eyes — crowded and dark. The skin around them creased and dry as chalk. I remember thinking he must have finished crying a long time ago.

I knew what they did in there, behind those high walls. My father told me when we first arrived. You had to use your imagination because we heard no sounds, and all we could see were the chimneys. But I knew. Everyone knew about the chickens. And then of course there was the smell.

My father said the chimneys were supposed to carry the smell high above us into the clouds. It was true, on some days especially in winter, the air could seem quite clear. But most mornings I would wake to the smell of gall, an acrid, musty heaviness which burnt the back of my mouth. We kept our windows closed. Curtains too. Weekly my mother replaced fresh potpourri in the bowls in each room. I felt sad sometimes, as I watched her, patiently crumbling petals, hanging her roses to dry, crushing lavender.

Once I said, "Mum, we'll never hide the smell, will we?" She tried to smile but I knew.

"We must try, my darling, mustn’t we?" And she did try, endlessly. She baked us scones, simmered home-made jams and lemon butter. When my mother cooked, the house was for a short time filled with the most replenishing aromas. Burnt butter, whipped cream. I would lean my head back and inhale deeply. But anything left standing for more than an hour tasted of a fleshy sweetness which tightened my stomach.

"What happens to all the chickens?" I asked my father one evening. I think he must have been expecting the question because he answered without pause, without even glancing at me from his newspaper.

"People eat them."

"Do we eat them?" I asked.

"No, we don't eat chicken."

Why? I imagined asking. But something in my father’s voice warned me off. And then there was the man in the olive coat.

News came one day that they were going to build another chimney. The chimneys were working to full capacity now, and the town had swollen with the families of those who worked there. Families like ours, chasing promises. More people meant more chickens were consumed, and that meant greater output for the factory. So more people were brought in to meet the demand. It was a celebrated cycle.

My father was an engineer, and they had called on him to design it. This was a great honour, my mother told me. They wanted to build a new chimney, four times as large as the others, and twice as tall. "Maybe this will finally free us of the smell," he beamed, and seemed shyly proud to be responsible for ridding our town of its oppressive fumes. He yearned for something I couldn’t possibly grasp as a child. Not praise, not even recognition — simply to be seen. To be visible. To leave something standing.

During those long days when my father worked at home on his plans, I had to play outside in the dirty snow and took to sitting in our plum tree — it had never borne fruit — or standing in the space nightly occupied by the mysterious man in the overcoat. My father had planted many trees in our modest garden when we first arrived. But few had taken, and most withered and drooped leaving us with an unhindered view of the chimneys.

"What does he do there all day?" I asked my father one night.

"Leave him alone. He's mad," Father warned.

"Nobody knows," my mother reassured me. "Best to leave him be."

But I was unsatisfied, and one cold evening, with the brown snow drifting to the ground, I asked him. I asked him why he stood there. And he turned slowly to look down at me. His eyes were dry, their sockets leathery and grey. "I am counting chickens," he said hoarsely.

"How do you do that?"

"Every minute, ten cubic meters of smoke leave the chimneys. That represents the remains of around 240 chickens."

"What do they burn?"

"Whatever cannot be eaten or used - beaks, claws, ribs..."

I stood for a long time without speaking. The man in the olive overcoat returned to his counting; the snow was burying his boots.

Finally I had formulated my next question. "The chimneys, they burn all night every night don't they? Can't you work out at home the number of chickens?"

Again I waited fearfully, stubbornly, the long moments for his reply. My toes were frozen. When it came, he spoke gently, as a doctor might offer explanation of an illness to a psychiatric patient.

"When I first made my calculations, I did make them at home. I lived a long way from here, in a town where clear air streams in from the sea. I made my calculations, and when I saw my answer, I could not imagine it. I could not hold so large a number in my head. So I came here to see for myself, to see the chimneys. And then…” His eyes dropped to the snow. “And then I could not leave." I wanted to ask why. Why couldn’t he leave? But something made me afraid of the answer.

The new chimney changed my father. He spoke to no-one for days at a time. Mother baked and he would return his scones untouched. When he went out, he would return laden with heavy bags, and my parents would argue in the kitchen. Their rows scared me and I’d retreat into my bedroom.

My mother baked more than ever, but these were new strange dishes, casseroles and pies. Her sweet sauces could not disguise the bitter chewy pieces we found inside. Often my mother and I were forced to withdraw gristle and chips of bone from our mouths, and I watched for my father to complain, but he ate silently and never left a scrap. I felt I was witnessing my father change, like a great tree with the coming of winter.

In the end, my father’s chimney was completed. A small crowd gathered outside our house and craned their faces up into the cloud. The tower stretched like a great arm up into the ashen canopies which always hung suspended over the other chimneys. It was impossible even to guess how far beyond the cloud the new chimney reached. My father was praised, and we felt a warm pride. Only when the crowd had dispersed did I notice that the man in the olive overcoat was not there.

Nobody ever again spoke about the man in olive. Our town grew more prosperous, many new people were needed to run the chimneys now. My father said production had been quadrupled. The smell remained. If anything, it grew stronger. But I knew better than to question my father — he was so proud of his achievement.

The years passed and as a young man I found work at the town's newspaper. The smell of ink offered temporary relief from the air. It was while researching a story that I came across an old photograph, unmistakable, of the olive-coat man. I had all but forgotten him.

When I traced the address, I found a decaying ramshackle house, boarded and nailed shut so that I could not gain even a glimpse inside. I returned that evening with crowbar and torch and had little difficulty prying away several boards barring the back door. Inside, the stench was overpowering. It was as though so many years of our putrid air had accumulated, waiting to release their odour. Pressing my nose into my hand, I panned the room with the torch-beam. Stacked against the walls, box upon box overflowed with notebooks. Where there was space, makeshift shelves had been stuffed and wedged full of innumerable books, stratum upon stratum, like an exposed rock-face. Each room conceded the same sight: neatly at first, then in increasing disarray, boxes of all sizes leaned and nodded under their loads. One door at the end of a corridor, I could open only a fraction, so jammed full was it of boxes.

I snatched up a notebook randomly and blew at its dust. Thumbing through its brittle pages confirmed my guess: each page bore a date and time-span, and simple scrawled calculations in a child-like handwriting. March 19. 8:40pm - 11:50pm. 190 mins. x 240 = 45,600. As I lifted the torch the beam caught a dust-caked mirror and I jumped. For a chilling moment I had thought it reflected the overcoat man. But it was me.

When I reported my discovery to my boss, the house was declared unsanitary and promptly torn down. What became of all the notebooks, I cannot be sure, but there was shortly after that an evening when my father’s chimney lit the night sky purple for several hours.

I am informed today that the factory is to build a new chimney. My boss thought I would like to write the article because of my personal connection. Were my father alive, it is hard to say whether he would be proud or disappointed that a young engineer is proposing a new chimney twice the size of his.

One thing I am certain of is that the smell will grow worse. But I am loathe to say anything. Hardly a day passes now when I do not think of the man in the olive overcoat. Rarely a night when I do not dream of a place where clean air streams in from the sea. But what can I say? I have good work here, I am known and liked. My children play happily and seem unaware of the air they breathe. And my wife prepares the most wonderful chicken dishes - she boasts no organ is wasted. I could never tell her how I long for my mother’s scones.

There are nights when I catch a glimpse of my tired eyes in the mirror. There are nights when I doubt whether the man in the olive overcoat ever existed. But I open the bottom drawer of my filing cabinet, and carefully lift out the notebook I kept, and I thumb through the pages where his small hand pressed the pen so firmly into the paper, and I know that he was real. He was there, and I saw him, and I see him now.

My children like to visit with me the pretty cemetery on the town’s outskirts. We tidy my parents’ graves. My children place flowers. It is a happy place. Ambiguity can also be truth, that much I know. I do not complain.

© Copyright 2025 Brendan Craig

About the Author

Brendan Craig is a Melbourne writer and poet whose work has featured in Quadrant Magazine and Quillette. He has tried his hand at Teaching, Magic and Parenthood only to discover they are the same thing.