by Emma Campbell

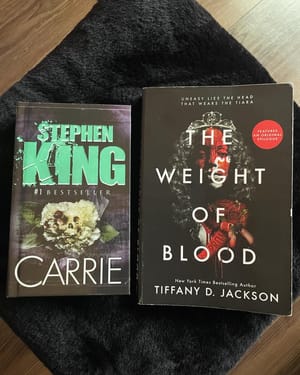

I’ll start this review off by admitting that I haven’t read a lot of Stephen King. My most recent foray into his work included me starting and then putting down Misery because it stressed me out too much. I consider myself a horror reader despite this, and am by no means against reading more Stephen King in the future. I picked up Carrie because I had already purchased The Weight of Blood by Tiffany D. Jackson and decided it was worth understanding the YA novel’s source material better - all my knowledge of Carrie stems from hazy memories of the movie. This resulted in an inadvertent study of the ways in which updated stories can use the same (or similar) tools to teach the same (or a similar) lesson while still keeping content fresh, relevant, and exciting. While Carrie was a good read for its originality, use of multiple documents, and dramatic irony, The Weight of Blood shone brighter in comparison - specifically because Jackson manages to tell the same story that King tells, but with a needed lens of intersectionality that necessarily and satisfyingly updates the content for a modern audience.

Carrie is a well-known story, partly because King’s works are so popular, and partly because the movie itself is part of the collective zeitgeist. Carrie is a repressed teenager who lives under the thumb of her abusive, ultra-religious mother, and who is bullied often for her looks and odd mannerisms. She develops telekinetic powers the moment she “becomes a woman”; this is the well-known shower scene in which Carrie starts her period, believes she is dying, and is mercilessly taunted by her classmates for her erratic behavior. It is punctuated throughout with descriptions of the blood everywhere - from the tile, to Carrie’s legs, to the gym teacher’s white shorts. This moment kicks off a string of events that eventually lead to the destruction of the town and most who reside there, including Carrie herself.

In The Weight of Blood, parallel character Maddy’s telekinesis actually jumpstarts with rain instead of blood - an immediate departure from the source material. In fact, The Weight of Blood, despite its name, scarcely mentions blood at all until the gory descriptions of Maddy’s destruction at the end of the novel. Maddy’s pent up anger and eventual release of telekinetic energy is in response to bullying from classmates, as well, but Jackson adds another layer here: Maddy has been passing as white her whole life. The rain (which she usually fastidiously avoids) makes her hair frizz and grow larger, essentially uncovering the secret her father makes her keep: she is half Black. This is the basis of the entire novel, and how Jackson updates the story for present day: the bullying becomes racial abuse, and depictions of how this racial abuse affects multiple characters, not just Maddy, makes its message even more relevant to the modern reader.

I enjoyed reading Carrie because it interspersed “real-life” documents into the story, such as excerpts from books on telekinesis, testimonials from survivors, the AP ticker, abridged versions of a character’s book, and even a Report of Decease. These documents create tension for the reader: each new document adds bits of information about the final events of the book, but only glances. The reader knows that something bad will happen in the end, and therefore is watching the narrative unfold with the understanding that every building moment is a clue foreshadowing this looming event. This dramatic irony draws the reader in, because the reader knows something the characters in the main narrative do not: most of them will not survive to the end of the novel.

What I did not enjoy about Carrie was the seeming preoccupation with menstruation. Yes, of course blood has to be a part of the narrative - it shouldn’t be lost on the reader that the biblical loss of innocence represented by menstruation also results in a literal loss of innocence and life within the school and the town. I mean, this book is positively soaked (!) in bloody imagery. But man, the focus on this aspect of Carrie and her blossoming into power (by way of her telekinesis, not her womanhood, necessarily) felt like way too much to me. And honestly, in the last few pages of the novel, just when I thought we had gotten past all the discussion of menstrual blood, it pops up again, described as flowing down the leg of another character. I need to be clear: I understand that this is King’s narrative structure at work. We begin with a period, we end with a period; the periods both have different meanings for the characters but both result in some loss of innocence; blood begets blood, trauma creates trauma. But first of all, I have never known anyone who starts their period with blood flowing so heavily down their legs that they can feel the trail and didn’t have any inkling that it was coming at all. And secondly - could we have maybe spent less time on describing teeangers’ menstruation and more on the town’s destruction? Horror is meant to make you feel lots of ways - I don’t think frustration at having to hear about period blood again is the fault of the genre so much as it’s the fault of the author.

The Weight of Blood, in contrast, is actually focused less on literal blood than it is on bloodlines: who are we, if we repress our natural selves? Who is forced into this repression? And what should we expect to bear witness to when someone breaks from the mold they were forced into from the start?

What I love about these questions is that they are similar to the questions King posed in the 70s to an adult audience, but here they are being posed to a younger audience: The Weight of Blood is, after all, YA horror. The ideas and themes in this book should be absorbed by everyone, but it’s helpful to have a parable like this for young people to begin, continue, or enhance their understanding of race in America.

And honestly, The Weight of Blood is a straight-up scarier book than Carrie is, mostly because of its relevance, and particularly in two aspects: the first-person accounts of survivors, and the fact that the villain of the story survives. In the most chilling first-person survivor account, we read a sort of play-by-play description of the events that occur when Maddy is exacting her revenge, told by a student who is trapped against the wall and can see everything. In this section, he describes a moment where, after most of the carnage is over, Maddy walks by him and looks him in the eye while he pleads for his life. This scene, whether purposefully done or not, holds the type of fear that is reminiscent of a school shooting scenario. It shook me in a way I was not expecting from a YA novel, but it makes unfortunate sense that a scene that resembles a school shooting - albeit in a much less realistic way, involving telekinesis and pyrokinesis - would be a fear that a young adult reading this book may have, consciously or not.

When we learn that the villain survives the carnage in the story, we deal with another detail that is terrifyingly relevant to modern audiences. Jules, who instigates the majority (though it needs to be said - definitely not all, which is a detail both authors specify in their respective tales) of the bullying and racial abuse directed at Maddy (and other Black students) is spared from death. She lives and doesn’t learn a damn thing from the experience, continuing to insist that she is the one who has been wronged. Again, Jackson creates horror in the everyday: how many times have we seen an instigator, a person with a gun, an individual spewing hate, who gets to be the one who comes out not only alive but often with a larger platform from which to announce their views?

Jackson uses a similar narrative structure to King, creating a story from multiple POVs and including documents that tell a deeper story than we can expect from one narrator. Some updates include a true crime-style podcast, Buzzfeed articles, Twitter updates, and sworn testimonies in place of the books, reports, and news updates in the original. These create tension the same way the documents in Carrie do, and they serve their purpose in breaking up the narrative to give glimpses of the horrors to come.

A final interesting aspect of each story is the use of color to represent trauma, oppression, and eventual growth, and when and where this imagery presents itself. King uses red to depict important moments in the story: the red of Carrie’s menstrual cycle, the scarlet eyes of “The Black Man” depicted in the bible and whose picture plasters Carrie’s dreaded closet, the red dress Carrie wears to prom, and the pigs’ blood dumped on Carrie at the end of that prom. Carrie’s mother reminds her constantly that her menstrual cycle is indicative of evil, that her red dress is evil - that Carrie herself is evil. There is no escaping this connotation, and it is reinforced often throughout the novel. Similarly, color is important in The Weight of Blood, but in this case, black and white imagery haunts the reader instead of red. This makes sense based on the story being told: Maddy is half Black and half white, so these colors take on greater importance to both the characters and the reader. When she is denying who she truly is (because she has been forced to her whole life), Maddy imagines something “ugly, inky black” chasing her down the hall; the fearsome hot comb’s iron is blackened from use. Things that Maddy is supposed to feel positively about (but doesn’t, necessarily) are white: her apron for cooking her father dinner every night, her father’s work shirts, the images of white women plastered in her own dreaded closet. As Maddy accepts her identity, choosing a life for herself that she wants to live, she also chooses a black prom dress, echoing her ultimate decision to embrace a suppressed part of herself. The last time we see this use of contrasting color precedes Maddy’s final act of destruction: she is drenched in white paint, as opposed to red blood, and the color here is a choice, too.

The Weight of Blood is a retelling of Carrie in its most basic plot, and Jackson clearly is not afraid to draw deeply on King’s original story to create a bold new vision for how we might ingest stories about trauma, abuse, and identity. Jackson ultimately succeeds in updating this horror classic from a tale of blood to a tale of bloodlines - and allowing readers of all ages to ask themselves: how do we carry the weight of our blood and the weight of our choices?

If you enjoyed the movie Carrie or if you’ve read the original book, I would recommend The Weight of Blood for updating old content in a way that feels both interesting and necessary. If you haven’t seen or read the original Carrie, I still recommend The Weight of Blood for its message and its inherent horror. While I am open to reading more Stephen King in the future, I am definitely planning on reading more Tiffany D. Jackson first.