by Ai Jiang

You and your best friend are divided into two lines: one comprising of those with previous experience with band instruments and the other made up of those without. Since elementary, your best friend has played the clarinet while you’d only done piano—though not anymore.

You consider asking if you can play the triangle, or the wood block, just so you can stay with your best friend, but you already know the teachers won’t allow it. So, you stand, watching your best friend’s line flow into the classroom next to the one you’re filing into.

“How lucky.” Your best friend sighs. “I want to be in strings too.”

The smile you offer is weak at best. “Yes… how lucky…”

But in your mind, you’re afraid. Afraid to learn something new yourself. Afraid that you won’t do well. Afraid you might fail without your friend because she is always the one leading the way. Afraid—

“Let me know how it goes!”

You laugh and say yes. Of course, of course you will.

#

Everyone takes a seat in front of a music stand already propped up. The eighteen students sit in two half rings around the teacher standing at the center, waving her conductor’s wand to take a headcount after attendance just in case someone decided to skip and had their friend cover for them.

Then she makes her way to each student, asking which instrument they’d like to play. Almost everyone leading up to you answers: “violin.”

When the teacher reaches you, she asks you to raise your hands, first palms up, then palms down. She hums with a small smile, tapping at each of your fingers. The contact makes you grimace, uncomfortable, even if brief. This is the first class after all, and you’ve only known this teacher for less than ten minutes. You don’t even like hugs from your friends and have never gotten hugs from your parents.

You prepare yourself to give your own answer, to add to the uttered chorus of violins when she meets your eyes, widens her own, smile stretching, eyes creasing until the whites disappear, irises covered by the folds of her eyelids pinching downwards, her pupils almost completely unseen but not quite.

She takes your hands in hers just as you’re about to lower them, clutches on a little too tight, and you resist the urge to pull away even as the spaces between each finger and your palms begin to clam, dampening your teacher’s dry, grainy skin, crinkling like tissue paper used for presents.

“Your fingers are so soft and slender and long. They remind me of when I was your age,” she murmurs. You aren’t sure if she means the length or the fact yours have yet been callous-broken or weathered with age.

The whole interaction is so strange, so disconcerting, that your eyes dart around like cornered prey to see if any of your other classmates noticed, but no one’s looking at you except for your teacher.

“Your hands are perfect for the double bass or cello. What do you say?” she asks.

Your eyes flick over to the towering string instruments sitting in the corner. Intimidating, with their endpins protruding. Your gangly and muscle-less arms can’t possibly hope to keep them steady and upright even though your teacher insists they’re light. The teacher’s smile wanes as you shake your head, first slow, then vigorously. And you try again, to join the chorus, to say, “violin,” but before you could, the teacher’s clutching at your hands again.

“What about the viola?” she asks. “Just slightly bigger, not so different from the violin. What do you say?”

You want to say no. The teacher herself plays the violin, so why does she want you to take up the viola? Especially if she said you’re so much like her. No, you won’t do it. But the longer the two of you are staring at one another—you with fear, her with desperate hope—you find your lips forming words you wish you could take back.

“Okay.”

The teacher gives your hands a squeeze, too tight, too eager, before she lets go, and somehow, next to you, she manages to convince your classmate to choose the cello.

The two of you look to one another, then share a long sigh.

#

“Isn’t it a bit much? To give us a test after just a week?” your classmate huffs, switching the handle of the cello case from hand to hand, almost smacking you a couple of times in the process, as the two of you trek to the bus stop.

The viola doesn’t seem so bad now, clutched in your right hand. The instruments themselves aren’t particularly heavy, but the old leather cases that the school keeps them within…

“I still have to bus another two hours home…” Your classmate rolls her eyes, pressing her lips together so tight they disappear.

“At least we don’t have the bass,” you say.

Your friend scowls but agrees with a solemn nod.

#

You realize the first of your problems in choosing the viola when you reach home, return to your room, open the instrument case and pull out the sheets of music. The score is written in the alto clef, unlike the violin written in the treble, the same as the piano. You’d already had trouble with piano previously, being unable to sight read no matter how hard you tried to memorize the note position on the sheet music, chanting FACE, FACE, FACE, FACE, FACE every single note you struggled to play on your right hand. Even worse on your left, because you had to say the entire EGBDF sentence in your mind—Every Good Boy Deserves Fish.

Always when you learned a new song, you’d ask your piano teacher to play the song for you twice, three, four, five times in hopes you might be able to remember the order she pressed the notes in and how the song should sound rather than trying to sight read, nausea washing over you, churning your after school meal in your stomach like gnawing air sickness upon a plane’s take off.

You remove your viola from the old, musty leather case, already tuned when you signed it out after school. Release the bow, tighten it, slide the rosin over the horsehairs before setting it all back down. You have no stand at home, so your windowsill serves as a makeshift as you set your score onto it, pencil already in hand. If you can’t memorize the notes, you’ll just do the same as you’d done for piano—label them.

And so, you begin again, FACE, FACE, FACE, FACE, FACE, except marking it one note after to transpose it into alto—F becomes G, A becomes B, C becomes D, E becomes F. When you’re done, you put down your pencil, pick up your viola, nestle it under your chin and the bottom of your left cheek, left wrist and fingers curling around the neck. Even before you raise your arm, you already feel the exhaustion and forthcoming cramp. You pick up your bow and hold it the way your teacher taught you earlier that day, reminding you of the way you hold a Chinese calligraphy brush.

You cringe with each note you play, some too soft, some too harsh, most of the sounds a squeal rather than bearing any semblance to the elegant music your teacher demonstrated in class, even though it was a simple scale, until your playing sounds passable.

The brief success quells your fears for the upcoming test—just a little. You smile when you’re called for dinner. With the bow loosened, viola back in the case and secured, score also folded and shoved in an inner pocket, labelled notes erased, of course, you skip your way downstairs.

#

“You can’t continue to label your notes,” the teacher says with a tsk, a disappointed furrow marks the middle of her forehead. “I’ll let you off this time, but next time, I’ll have to lower your grade.”

Across the room, your classmate fidgets under the teacher’s scrutinizing gaze.

These very words remind you of what your piano teacher had said to you when she first discovered you’d been labelling your sheet music. She’d been puzzled at how you’d managed to elude her of the fact for seven levels (untested of course) until it was time to formally take RCM level eight, and you’d gotten every single note transcription wrong on the theory practice worksheets that she told your mom it was hopeless to keep trying.

Your breath quickens as you skim over your score for any remnants, signs that you had also labelled your notes. But there is no trace of graphite from your pencil. You’d marked it light enough that your teacher shouldn’t be able to notice what you’d erased.

Your classmate glares down at her cello’s endpin as though she’s contemplating lifting it from where its sharp tip nestles into the dirty carpet so she could stab the teacher’s retreating back. Her hand twitches against the strings and the endpin sways, subtly, side to side, lifting before jabbing down a handful of times as the teacher begins to test another student.

You wish the two of you still sat next to one another, but the teacher divided the room by instrument, so all you could do is smile in sympathy when your friend’s glaring eyes meet yours before they soften and roll to the back of their head.

#

You pass several tests, and you thought this would be good enough for an above average grade in the class, but what you don’t expect is your teacher holding you back when the bell goes off so she can ask you to be the first junior of the year to join Senior Strings and the Orchestra—as first chair. She’s giving you that same smile again, clutching at your hands, whispering, Soft, slender, long, as if you couldn’t hear her. So of course, you say, “Yes,” even though you know that this is a mistake.

And you realize this mistake when you walk into Senior Strings practice for the first time after school and your teacher announces, “We will sight read the five pieces we’ll play for the eighth-grade graduation in two months.”

It took you the entire month just to learn each song for the class tests leading up to joining Senior Strings.

Five.

In two months.

You can’t keep labelling your notes.

But you must. You have to. You have no choice.

You hunch over and tell your teacher that you have a stomach-ache, so you’ll have to bring the score home to practice instead before you hurriedly sign out your viola and rush out of the room.

#

In a hurry, you know you’ve marked up all your scores too harshly with the notes, practiced until you’re no longer holding your viola upright but have the top of it resting on your knee, elbowing trying to do the same. The upright position of your wrist is collapsing, and you keep dropping your bow arm.

You shout in frustration when you get to the fourth song and your muscle memory refuses to remember anything you’ve just practiced. Your fingers begin to tremble, and all you hear in your mind is a jumble of notes from the three songs you’d practiced and the tick-tocking of the new metronome your mother purchased, saying it might help you with practice, but all it has been doing is reminding you how off your rhythm is, how you’re playing too fast or too slow, every second you’ve wasted when you make a mistake, and then the same mistake over and over and over and over—

#

You trudge into Senior Strings practice after school—sleep deprived. Your classmate is already set up, so they come to watch you do the same while the teacher is out of the room. With shaky hands, you pull out your viola and bow and throw your score onto your stand. As you tighten your bow, your classmate gasps.

“What—?”

Then you see what she sees. The score, all labelled still, letters deep and dark. You scramble for your eraser but realize you’d left it in your backpack left in your locker just as the teacher walks into the room.

“Shi—” Your classmate rushes to her seat and hurries back with something in her hand. It’s on purpose, but you’re still surprised when she pretends her toe catches on your stand, and she splashes an open bottle of juice onto your score.

The teacher says nothing, but you could tell that for a second she is squinting, scrutinizing your sheet music even though they have flopped over, obscuring the contents of the pages.

“Oh, I’m so, so sorry!” your classmate says as she splays her hands over your drenched, sopping sheets, scrunching them in an effort to “wipe” off the juice.

The teacher’s eye twitches as she watches the interaction unfold, her mouth too trembles, before she plasters on a smile.

“Looks like there’s been a bit of an accident.” The steely glare she fixes on my friend doesn’t go unnoticed as the entire room, though there’s only eight of us in total, hold our breaths.

Your classmate chuckles nervously before heading for the washroom for paper towels. You thank her in silence and know that even with all her transgressions, the teacher needs her for Senior Strings. After all, she’s one of the three cellos in the entire school.

#

“Why don’t you just print another copy?” My classmate winks at me.

Yes, why didn’t you?

You feel like a fool for not thinking of this earlier. So that is what you do when your teacher gives you new scores. You photocopy several sheets so you can use the labelled version at home and bring the unmarked one to school. But that doesn’t help because no matter how many times you go through the songs at home, you freeze, nerves chewing at your fingers and mind whenever you get to practice.

Orchestra is worse because there you see your best friend. There, she’s playing the clarinet with ease, something she’s been doing ever since elementary. You wish that could be you, but you know it can’t. She has the kind of smooth confidence that can’t be practiced, one that is only born with.

“Well done,” the teacher says when practice ends, and you’re lucky she’s only been making everyone practice the easiest of the five songs first: Pachelbel’s Canon.

Still, your back is drenched the entire time, and you wait for everyone else to get up and leave first before you yourself pack up, hoping no one noticed the darkened colour of the damp back of your shirt.

“Marvellous performance.”

#

You’re the first junior to join Senior Strings and the Orchestra. First chair, before they added three more, two from your grade and one from an upper grade two weeks later.

They are better, much better than you—all three of them sight read all five songs on the first day they joined practice while you still struggle with the remaining two.

And that is when you started to fall, from first chair, to second, to third, to fourth—last, really, since there are only four violas.

But somehow, you feel relieved.

But that is when the hand first appeared, and when your hair began falling.

#

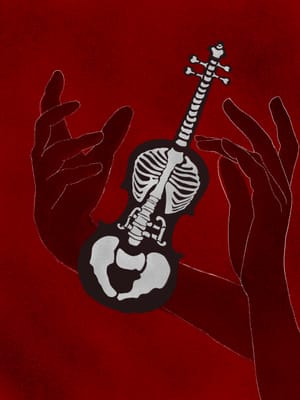

The hand first appeared when you returned home to practice the fourth song again, wrapping over your own hand clutching onto the neck of your viola, holding on iron tight until the strings slice through your built-up calluses, until blood coats the strings with your fingerprints.

Who needs muscle memory? the hand whispers. Here, I’ve marked out all the notes for you.

And it did. You know exactly where all the notes are now, not a single waver as your fingers glide across the strings, pressing down on the blood now dry, becoming rustic. But at the end of practice at home, you make sure always to wipe away the blood before returning to school.

“Are you okay? You seem—”

“Fine, perfect. Perfect.”

You smile, and your classmate flinches, shrugs, and slinks away with her cello.

#

Your left hand isn’t the problem now but what you clutch in your right.

Your bow, old and squealing, makes every note less elegant than they should be. You remember what your teacher said, “Soft, slender, long,” and how she didn’t just look at your fingers, but also at your hair, as if she wanted nothing more than to brush it like Rapunzel’s mother, take it for her own.

So, you begin to pluck, first just strands, the longest ones you have that match the length of the bow, and you weave them in with the horsehairs, rub the black and white with rosin. Still, the notes shriek and squeal. So, you begin ripping out hair from the base of your head in clumps so only you will know what you’ve done. You rip the white horse hairs from the bow, replace them all with your own. Tighten it, rub rosin again.

This time, each note sings.

Soft, slender, long.

#

“Is that a new bow?” your classmate asks when you walk into practice.

“Ah… yes. The old one broke,” you say, and when your teacher passes by, you look up at her with a shy glance, begging for approval. “I hope that’s okay.”

She smiles at you, that same smile she gave you on the first day of class. The same one she gave you when she asked you to join Senior Strings.

At the next practice, you are first chair again.

#

Yet still, the only song you can play perfectly is Canon in D. The others are still too difficult, but manageable, especially now with three others to hide all your shortcomings. Sometimes you find yourself peeking over at your fellow violas instead of looking at your teacher’s conducting or at your own score, shadow-playing instead of actually playing, until you look back and notice your teacher’s sharp eyes training on you with a feverish glare.

You stare at your strings, imagine the crimson prints on each, glance at your silky bow becoming greasier, stiffer and crustier, each time you apply rosin, until practice is over, and you can breathe long and deep instead of shallow and short.

But before you can leave, your teacher halts you by the door.

“I have something I want to speak to you about.”

You trudge back, slow, weary, wondering if she might demote you from first chair again, wondering if it might actually be better if she does, especially with only a week left until the eighth-grade graduation.

“I want you to perform a solo. Very short. Just three minutes. At the graduation next week.”

You freeze.

“That won’t be an issue, will it?”

You want to tell her to give it to someone else. Yet you feel the hand crawl up your arm, hop onto your face, its fingers prying at your mouth, tugging your lips upwards, shaping the words for an answer in your stead, “It would be an honour.”

The score is in your hands before you even finish your sentence.

#

Canon in D runs about six and a half minutes, but the teacher makes you and the rest of Senior String play it three times, without prior warning, because of how slow the entire eighth grade files into the hall for graduation. That’s the longest any of you had to play without a break. By the end, when it comes time for the four other songs, your arms are on the verge of collapse.

But you still have the solo.

And in your mind, you whisper a plea to the hand, who has become more than just a hand, but now owns a face that whispers to you each note in place of the score, with a secondary mouth and clucking tongue where its chin should be, working as an internal metronome instead of your teacher’s conducting.

Play for me. Please play for me.

You beg the shadow with each song passing. Hidden behind all your sheets is the solo, unmarked, but you didn’t bother to wipe the dried blood from your viola strings, and the sight of it seemed to excite rather than repel your teacher towering above you all like a god passing judgement.

Your arm is cramping, held up only by the hand and its smiling face.

The drone of strings blends in with the droning of the face. Each whispered note and metronome rhythm that escapes its double mouth sounds like a repeating mantra.

The bald patches hidden under your long hair, strands you uprooted to make yet another new bow, itches, and you can feel the growing rash—red, angry, clawing.

You should’ve stayed fourth chair.

You should’ve—

#

You begin your solo, or rather, the hand does it for you, fingers gliding across and along the neck of the viola. You look to your teacher, for praise, for acknowledgement, but instead of the glorious idol standing in front of her stand, what you see are the stains of yellow at the pits of her white shirt, and you wonder if you look the same.

What you notice now is not the neatness of her slicked back hair but the patches of baldness in which it hides. Your fingers twitch, almost stray from the notes of the solo to touch the base of your neck where hair is missing, but the hand doesn’t allow you.

But the more you stare at your teacher, the more you wonder if your teacher chose you because you reminded her of yourself and she herself was never chosen when that was all she’d ever wanted. Yes, your fingers are long, but are weak, your arms too gangly and awkward, your played notes wispy and meek.

And that is when you notice the teacher’s smile straining. Then you start freezing up, getting lost, and suddenly you can’t keep up with the tempo of your teacher’s conducting that seemed only to get faster and faster because it no longer aligned with the tic-tocking of the metronome in your head. She’s doing this on purpose. To test you. Surely.

Right next to your ear pounds the vibration from your strings, along with the grainy squealing that sounded so elegant only moments ago, now like pigs stuck in a pen, splashing around in the mud as if looking for something that they have no hopes of finding. The hairs on your bow, with each sawing motion of your arm and wrist, back and forth, back and forth, start to fall apart, the strands of your hair fluttering onto the ground around you.

You hear the scrap of an endpin against the wood of the stage, back and forth, back and forth, and know it’s your classmate. You’re on autopilot now, mechanic, wooden, jerky like there’s something stuck in your joints—the terrible, terrible music, no longer music, sounds like hoarse screams coming from your viola. And the face staring at you from the score is no longer chanting a calming mantra but shouting obscenities that are clouding your mind.

#

When you finish, you know you’ve failed, because there is no clapping, no one rises when you rise. The hair that found its way onto your white dress shirt from your bow now loose, scattered, broken, falls onto the ground, collecting in a pool like dripping shadows around you, and the hand lets go of your bloodstained viola, allowing its hollow, wooden body to clatter onto the stage, echoing, before the hand and face hovering as though part of a formless body unseen, steps from behind you, through you, rendering you paralyzed, hands frozen at your sides.

You’re the hand and face bows, smiles, with both its mouths.

Then the entire auditorium bursts into applause, but in your ear it’s all muffled, as though the sound is travelling from far, far away.

The teacher steps from her stand, stopping in front of yours, gesturing towards you’re the hand and face with a proud smile, and you couldn’t help but smile back even though you know she can’t see you, not anymore, or maybe this is the first time she is truly seeing you.

The hair that had pooled all around you is now gone, cascading down the back of the face, a strand clutched between the hand’s fingers.

Your teacher’s hand is reaching towards them, towards their fingers, their hair, whispering,

Soft, slender, and long.

Soft, slender, and long.

Soft, slender, and long.

“Marvelous performance.”

© Copyright 2024 Ai Jiang

About the Author

Ai Jiang is a Chinese-Canadian writer, winner of the Bram Stoker®, Nebula and Ignyte Awards, and Hugo, Astounding, Locus, and BSFA Award finalist, and an immigrant from Shanghu, Changle, Fujian currently residing in Toronto, Ontario. Find her on most social media platforms and for more information go to aijiang.ca.