by S.C. Mills

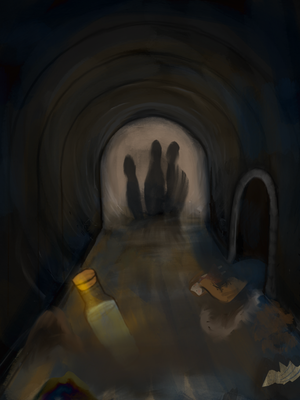

Sewage and stormwater rush past the monk’s corpse, streaking his ash-white robes a sickly, greenish gray. Dozens of people crawl around him in the cavernous sewer. Shadows from their oil lamps jump and flicker across the low brick arches overhead. Frances stands in the runoff, back pressed against the damp wall, frozen in fear of all the strangers. At least the familiar stench of her sewers comforts her. And at least Claudio is here, returning now from a whispered conversation with another worker.

“The holy man was bringing healing water from the sacred mountain.” Claudio bends down to her height, hunching his broad shoulders to whisper to her. “Guess somebody killed him for it.”

She squints at Claudio’s filthy face, soiled like hers from their shift together clearing blockages.

“We figure they’re all here to look for evidence,” he adds. “Or the water.”

Her eyes dart among the strangers poking at the waters. They’re scattered around the man’s body in the main channel. None seem to be checking the side nooks and crevices where objects carried away by the current may be found.

“Yeah.” He winks. “They aren’t so bright. We could—”

“You two!” A woman in ash-white robes and knee-high boots wades over. Her high voice commands attention. “Your supervisor says you were both here all night?”

“Yes, Prioress,” says Claudio.

The Prioress asks Claudio question after question. Claudio answers for himself and Frances both, answers on and on. While he talks, a robed man—the Abbot, who leads weekly services for the laity—joins them to listen.

“Enough from you.” The Prioress looks at Frances. “What’s your alibi?”

Frances shakes her head. All she did last night was listen to Claudio’s running mouth and the scraping sounds of their shovels, while counting each scoop of sludge in her head. Like knots on a prayer rope, up to ninety-nine and down again.

“She don’t speak, Prioress,” says Claudio.

“Not even to clear her name?” The Prioress looks Frances over, her tone skeptical.

The Abbot’s brow creases, but he says nothing.

Frances catches the Abbot’s eye, then looks pointedly between her tiny hands, gnarled with age and callused from the shovel, and the purple-black bruises and welts wrapping around the dead monk’s thick neck. Muscles swell beneath the well-fed holy man’s once-white robes, like mounds of sullied snow. Exceptional physical conditioning is required to survive the dangerous pilgrimage to the mountain’s frozen pinnacle, source of the healing water.

The Abbot nods.

“She’s too weak,” says the Prioress, who is herself a small, elderly woman. “She couldn’t have killed a man in his prime. Not alone.”

Both turn to Claudio, tipping back their chins to look up at him.

“Holy water heals the pure, but kills the unworthy, you know,” says the Prioress. “Like thieves.”

“I’m no thief,” Claudio huffs.

Frances aims her eyes at Claudio’s powerful hands, which carried all nine of his children to baptism. He’s a good man. Devout. Honest. And the Abbot knows him well. But the Prioress is looking at Claudio’s prayer rope, belted around his waist, knotted at the same intervals as the bruising on the monk’s neck.

The Abbot speaks for the first time. “He keeps a prayer rope with him, always, even at work.”

“Or he hides the evidence of his crime under false piety,” replies the Prioress. “A lie can be told by actions as easily as words.”

#

At the insistence of the Prioress, a lawman arrests Claudio. Claudio argues loudly, but does not resist. A chant repeats ninety-nine times in Frances’s mind: He’s innocent. He’s innocent. The Abbot should know it and pardon Claudio on the spot. Anger at the injustice burns hotter in her heart with every beat. Her hands itch to stop the lawman directly with a shovel to the head. Instead, she stands aside, trying to disappear in the shadowy sewers. Keeping herself out of trouble, for the sake of others.

She has no spouse nor children of her own to miss her. She’s never wanted a lover. But she does nothing, because she can’t be there for Claudio’s family if she’s sharing his jail cell.

“Find it, Frances,” Claudio shouts back to her, over his shoulder, as the lawman marches him out of the arched entrance to the sewer and into the harsh morning sun.

Frances stands alone, amid only strangers again. She was planning to run straight to Claudio’s wife, to their home, but—

Find it.

The detritus of people’s lives floats by her, catching her eye: threadbare rags, ruined tools, a child’s doll. Lamp held high and shovel in hand, she follows them downstream instead. If the monk or the killer lost the bottle in the waters, or lost anything that might be a clue, maybe she can find it.

Objects are more reliable than people. Evidence could clear Claudio’s name.

She pauses at every side channel where she’s ever unclogged a blockage, prodding with her shovel in the muck, finding what the sewer has snagged. A boot, worn to nothing. Shards of pottery, eggshells, splintered animal bones. She pockets a rusted thimble for Claudio’s seamstress wife. Then, she sees something like a prayer rope, but when she pulls it dripping from the water, it’s nine leather cords tied together, each with eleven knots.

She drapes it over her shoulder and carries on, checking each nook and cranny where she’s ever found a wayward treasure, counting and counting. Urgency presses at her. Claudio needs her help.

Her shovel scrapes something. Ethereal, holy ringing, like a xylophone struck in prayer, sings out in the dark. With a bare hand, she draws out a glass bottle of healing water. Mud slides off it, leaving it clean. It multiplies the lamplight like no mundane glass could, sending rainbows across the dripping walls and her own wizened, mud-streaked body. To survive its journey through the sewers unmarred and unbroken, the bottle must be fortified by contact with the holy water. Made unbreakable, somehow, in this place of broken things, where Frances belongs.

She has not been so fortunate.

A life of manual labor has worn on her. Her body has been sliced by broken glass, inviting infection, leaving scars like pink worms. She’s sick, always sick, from breathing polluted fumes and spending shifts wading through disease-ridden waters. Always alone, except for Claudio and his endless talk of his family’s triumphs and woes, of his hardworking wife and their leaky roof, of his children’s bright minds and hungry mouths. Frances helps them with every spare penny, keeping for herself only the least she needs to live.

But now, selfish desire slams her, unfamiliar and unwelcome, amplifying every ache in her creaking, aged joints. This water was destined for the city’s cistern, to be shared by all, but stealing one undiluted swallow now tempts her sorely.

She’s no thief. She’s never stolen, only given and given and given. What if she is worthy?

Her hands tremble on the cork. She slides her thumb along the edge of the bottle’s wax seal. It’s been broken and resealed before. She could open it again and serve herself a single glorious drop. Such an indulgent portion—compared to sharing with the entire city—might work miracles on her health. Might make her young again or even unbreakable, like the bottle.

No one but God would know.

#

Frances slogs through the city’s bowels toward the monastery, bottle in hand. Still unopened. As she trudges along, knees aching, her mind plods through everything she’s seen and heard and touched today, searching for some way to clear Claudio’s name. Turning the bottle in won’t suffice; it might do nothing but incriminate her, too. The Prioress’s words echo in Frances’s mind: She’s too weak. No one would believe Frances acted alone.

Maybe she’s dreaming too big.

Find it, Frances, Claudio said, as he was marched away. Not prove me innocent or fight the law or catch the murderer. No. In that frantic, fearful moment, he told her only to find it.

Getting the water into the city’s drinking supply matters more than her and Claudio’s fates, more than justice. To her, and to Claudio. She’ll worry about everyone first, and then about the family that’s become like her own.

By the time she reaches the sewers that run beneath the monastery’s pit toilets, resignation has settled down into her wet, weary bones. Yet, an ember of joy still smolders in her chest. She might spend her few remaining years in prison alongside Claudio, but after decades of mysterious failures, of solitary pilgrims and great caravans alike all gone missing along the perilous route to and from the holy mountain, at last the whole city will drink of its waters and be healed. At least a little, and in some part thanks to her. She only has to hand the bottle to the Prioress, and the rest is in God’s hands.

She turns toward the archway leading out of the sewers, toward the blinding midday light, when she hears a voice.

“Another pair of sewer workers have agreed.” The familiar soprano is only a whisper, but it carries down the pit toilets and echoes in the sewer below. “They’ll testify they saw Claudio away from his partner, alone, in the middle of his shift. That should do it. No one will doubt the steadfastness of our departed brother.”

“Worthy souls indeed.” A second voice—unfamiliar, creaky from disuse. “And Claudio’s partner?”

“That’s why we’re speaking, brother,” says the first. “I leave the care of that poor, feeble woman in your worthy hands.”

“I see.” A pause, a tapping of a foot on stone. “And if she did find the bottle?”

“Bring it directly to me, so—”

“So only the worthy might partake of it.”

“Just so.” Another pause. “God’s blessings upon you, brother.”

“And upon you, Prioress.”

Frances stands just within the archway, open-mouthed. Betrayal twists a rope around her heart and squeezes. She cannot take the bottle to the Prioress. She cannot take it to any of the monks—no one who might be addressed as brother. Perhaps not even the Abbot, though it pains her to doubt him. And she cannot hope to sneak unseen into the monastery and climb the tower to the funnel built expressly for this purpose, should any ever succeed in this exalted mission.

Not under the light of day, anyway.

#

Frances hunkers down to wait in the comforting damp darkness beneath the monastery. She’s exhausted, but rest is impossible. She holds unfiltered temptation in her unsteady hands. Above her, the nuns, monks, and other disciples visit the toilets, toss out their washing water, and go about their days. She envies them their unbroken routine; she longs for her own. Her stomach growls when the smell of their porridge and ale drifts down. After dinner, a syncopated, rhythmic thumping echoes around her. It mystifies her until she counts the beats: eleven sets of nine. The disciples’ nightly flagellations.

She stares down at the water bottle, at its imperfectly remelted wax seal. She fingers the knotted and joined ropes that she found downstream of the monk’s corpse. She touches the thimble in her pocket. The meaty thumps from above shake an idea to the surface of her mind.

Objects sometimes speak the same way she does.

She places her tools and findings against the wall and stands up. Her thin arm swings the filthy lost prayer flogger at her own back. Her weak muscles aim poorly. One strand whips around her neck. She drops the flogger in shock and touches the rising welts. She recalls the purple-black bruises spaced around the monk’s neck.

He wasn’t strangled. He was just a monk. A man of habit, even while traveling and tired. The marks around his neck were made before he died, not by what killed him.

The Prioress said holy water heals the pure, but kills the unworthy. Like a weary pilgrim at the end of a long, trying journey, yielding at last to the ever-present temptation to sip water to ease his aching body. His vows—silence, chastity, poverty—should’ve kept him apart from the world and in service to others, but perhaps instead they made him imagine himself more worthy than they.

He wasn’t. He hid in the sewers, and then, humbly aware that he might die, he resealed the bottle before sipping from a separate cup. Like she could do now with her thimble.

But he did die. Just like she would probably die, too, were she to follow his example. And now, Claudio will be punished for the monk’s selfishness, just so the Prioress won’t have to admit why her order failed yet again to retrieve the holy water.

Frances has said no vows. She wipes away tears with a grimy hand, gathers her evidence, and climbs out of the sewers to do what is right anyway.

#

Above, night has fallen. The monastery is dark and silent. Frances’s boots track muck across the white stone floors. She’s never sneaked in anywhere she wasn’t welcome, but she learned to step lightly tiptoeing around Claudio’s house while his babes slept.

Heart fluttering with anxiety, she makes her way unseen through the nave, where she goes with Claudio and his family every week for services. She slips through the unlocked door behind the chancel. The chapter hall here is utterly unfamiliar, but she counts her steps to steady herself and searches methodically for the tower stairs. The high cupola that houses the funnel is visible from the street below. She’s seen it many times from the outside, but the monastery is a maze of ancient architecture, of additions and walled-off halls and long dark corridors that lead to nothing. She wanders, tracked only by the lifeless eyes of painted or stone-carved saints.

At last, on swollen knees and throbbing feet, by God’s mercy, she finds the tower. She ascends more than ninety-nine steep stairs—higher than she’s ever been in her long life.

She emerges still unnoticed through an archway at the top of the stairs and into the cupola. Giant arched windows, open to the night air, ring an alabaster funnel. The white stone gleams and twinkles in the starlight. She takes a step toward it. She’s almost ready to call her luck divine when she notices she’s been spotted by two living, waking souls.

Not just anyone may dump just anything into the city’s cistern. Two guards in ash-white robes sit on the floor of the breezy cupola, huddled under coats and playing a game with cards by the light of a shielded lantern.

“Hey,” says one.

“Who’re you?” asks the other.

Frances gasps and freezes. These men are strangers, and they have swords, and she cannot explain herself to them. One of them might even be the man commissioned to her “care.” And she is so, so high in the sky, far above the sewers, and worst of all, Claudio isn’t here.

“Oh, hey,” says the first one again. “Look in her hand. The Prioress said—”

“Don’t just sit there!” They reach for their weapons. One steps between Frances and the funnel.

Full panic screams in Frances’s mind, driving out all reason. This is a holy place and the cupola has eleven arched windows and she circled it nine times during her painful slow ascension on the spiraling stone stairs and without thought, as if Another guides her hand, she thrusts the bottle out through the nearest window, so it dangles over the cobblestone streets far, far below.

Now, no one moves. Frances begins counting her own ragged breaths.

#

One guard leaves, and a cluster of people come back with him. They crowd the archway at the top of the stairs, peering over each other’s shoulders, raising lamps high.

At around five hundred breaths, the Prioress herself gets bold and comes too close. Frances has to act as if she might jump through the window to get the supposedly holy woman to back off. It’s the only lie Frances has ever consciously told. It works, though. After that, they all stay well back. And perhaps God has already forgiven her that falsehood. The ring of bruises now purpling around her neck might’ve been her atonement.

After that, they all stare at Frances and whisper to each other, like they might fix her and her outstretched arm in place with only their collective gaze. No one but her seems to know the water renders its bottle unbreakable. She doesn’t understand how they don’t know, at first, but then she figures it out from their whispering. No one has ever made it back from a pilgrimage alive to tell them. No one has touched the water and spoken of it to a living soul.

She waits, dangling the bottle high in the air, an empty threat that’s nonetheless effective. Sometimes the assembled monastics shout at her: pleas, threats, advice, prayers. She hardly hears them. She’s waiting for them to bring Claudio. The Prioress and the Abbot both saw how he spoke for her this morning. They will figure out how to handle this eventually.

In the meantime, she counts breaths and practices patience. Her arthritic fingers whiten and cramp from being held so high in cold winds, but the holy water comforts her and warms her in spirit. And perhaps in flesh, too—she does not lose her grip. Not for so, so many breaths, not even as the stars wheel across the sky out her window and a gibbous moon rises.

At long last, the right people say enough words to each other to figure out what should be obvious. Someone is sent off to the city jail. Later, Claudio’s strangely clean face emerges amid the crowd. Two thousand forty-nine breaths have passed. Frances stops counting.

Claudio and the Abbot step together into the cupola, but the Abbot stays back, lingering near the entry. He hands Claudio his lantern, and Claudio comes straight to Frances. He bends down to peer at her neck, frowns, then looks her in the eye.

“Knew you’d find it,” he says. “Nobody knows the sewers like our Frances.”

Frances grins. Her fatigue drops away. She can hardly feel her body at all anymore, in fact. It doesn’t matter. Her best friend is here.

“The Abbot came himself to get me from jail, you know. He’s a good man, Frances. He says you can pour it in yourself, if that’s it.”

Claudio’s tone shows he understands that isn’t the problem. Frances doesn’t even bother shaking her head to confirm it.

“Agreed. That’s sort of the least they could do, isn’t it?” Claudio looks over the side of the cupola and out the open window, at her hand. At the bottle.

Frances runs a numb finger over the wax seal, at just the place where the re-melted seam is most obvious.

Claudio squints. “Can I see it closer? It’s awful dark for looking at fine things.”

Her gaze flickers between him and the assembled. Claudio turns around. “Back it up,” he hollers, and to Frances’s shock, most do, though the Prioress is not one of them.

The Abbot makes a chiding sound and a shooing motion with his hands. For a long moment, the Prioress glares at him and doesn’t move. Then, she and those still with her also back down a few steps, leaving the three of them alone in the cupola.

Frances brings the water bottle back over the stone floor beneath her feet.

Claudio touches it with his big, meaty hands. He draws in a sharp breath. “That’s the real stuff, isn’t it?”

She nods, but lets her impatience show on her face. Her finger traces the seal again.

“Oh.” Claudio wets his chapped lips. His throat moves as he swallows hard. His hand cups the bottle. “It was opened. That wasn’t you, was it?”

Frances shakes her head. With her other hand, she points at the bruises on her neck and the wet flogger she dropped on the floor at her feet.

“I see,” says the Abbot, and Frances snaps her head to look at him. She forgot he was still here. He looks so old and forlorn, but his eyes are hard and eager. “I see. Our departed brother drank from the bottle himself, for selfish reasons. That’s why our expeditions fail: Those who survive the physical perils fail the moral test. They drink it directly, serving only themselves.”

So, that is what makes one unworthy. Or at least, that’s one way.

“And they die?” asks Claudio.

“They die,” the Abbot confirms.

Frances shivers. She came so close to failing, too. She looks at the funnel. Foreboding prickles along her neck—will the whole city’s faith be tested, as hers was?

“Even now, knowing all that, I still feel the temptation.” The Abbott leans forward. “I still want it all for myself. Part of me believes I would be the one exception. It wouldn’t kill me.”

“I want it, too,” says Claudio. He jerks his hand back from the bottle and backs away across the cupola, far from Frances.

The Abbot also takes a few small steps back. “Go on, friend,” he says to her. “I will make sure you’re exonerated.” He glances briefly back at the stairs, where the Prioress and a few friars are peering around the corner with sharp eyes. “I’ll investigate what’s been going on in my order, and I’ll pardon you myself if I must. Both of you.”

Frances stumbles forward on unsteady legs, too tired to feel relief. Something more like holy fervor drives her, compelling her to do God’s will. She rests her aching bones by slumping to her knees against the side of the funnel. She cracks the wax seal and twists out the bottle’s cork. It takes a long time. Her fingers are numb with cold and weak with age, but neither man offers to help. She shakes the wet cork over the funnel with three flicks of the wrist, like the Abbot did to baptize Claudio’s babes.

At last, in full view of God and His devoted, she pours the bottle of healing water into the alabaster funnel. Sending it into the water supply, for all God’s worthy and unworthy alike.

# # #

© Copyright 2025 S.C. Mills

About the Author

S.C. Mills writes speculative stories set in worlds that might be dark and fearsome, but where love is still alive and bright. Their characters find unusual and queer connections with each other and create the divine and holy from the mundane. They live in Seattle, where they like to hike in the dry season and train martial arts while it rains. Their stories are published or forthcoming in Heartlines Spec, MetaStellar, and elsewhere, and they’ve won NYC Midnight, Writing Battle, and exactly one paid grappling match. Find them at scmillsbooks.com and everywhere online @scmillsbooks.